2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(611e) Computational Modeling Suggests Recruited Immune Cell Clustering in Small Airway Disease Accelerates Fibrosis

Author

Respiratory diseases are responsible for many of the public health crises we face today, with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) being one of the most impactful. The World Health Organization states that COPD is the third leading cause of death worldwide (behind heart disease and cancer) which accounts for 3.5 million deaths annually. This grim statistic highlights a desperate need to investigate how respiratory diseases like COPD progress and determine where our immunological defences fail. To better understand how COPD develops, we investigate the small airways where the disease is thought to begin. Here, damaged lung epithelial cells release inflammatory cytokines to recruit immune cells like neutrophils and macrophages. Sustained inflammation leads to destruction of airway and subsequent formation of fibrotic tissue. We hypothesize that the distinct spatial patterns of macrophage clustering in the small airway walls lead to different airway remodelling outcomes, with clustering accelerating fibrosis and airway obstruction more than diffuse distributions.

Methods

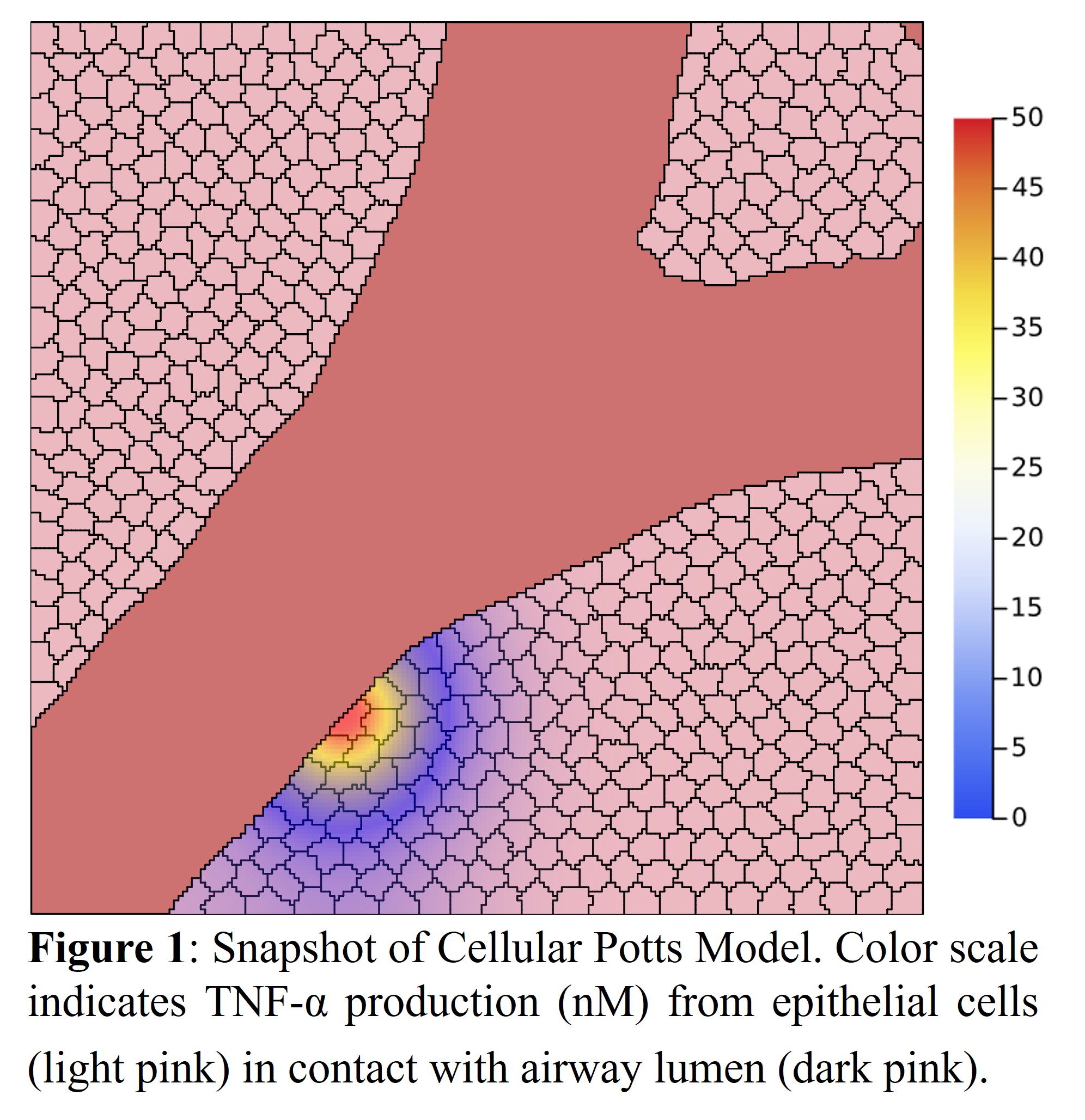

To test different spatial patterns of immune cell recruitment we turn to Cellular Potts Modelling (CPM). CPMs are coupled with partial differential equation (PDE) models to simulate diffusion and cell chemotaxis. Here, our model consists of four cell types (epithelial, M1/M2 macrophage, and smooth muscle cells), collagen, and particulates. When exposed to particulates, epithelial and smooth muscle cells begin to produce TNF-α (recruits M1 macrophages), TGF-β (shifts M1 to M2 macrophage), and undergo apoptosis. M1 macrophages can produce more TNF-α to sustain inflammation whereas M2 macrophages promote collagen deposition. Two scenarios where tested based on spatial variation in airway particulate concentration to encourage either uniform or clustered immune cell recruitment. Each scenario was repeated five times to account for variations across simulations. Fibrosis was quantified by total collagen deposition (i.e. number of pixels assigned to collagen). The dynamics resembled a logistic function, so this model was fit to each simulation. Mann–Whitney U tests were performed to determine differences in the model’s carrying capacity, growth rate, and inflection (midway) time point.

Results

In our model we measured cumulative collagen deposition for both low and high variability in airway particulates. In the high variability model, collagen deposition began sooner (at day two, p=0.013), and reached a maximum capacity sooner compared to the low variability model (at day six). There was also a significant difference observed in the growth rate of deposition (p=0.024) where the high variance model showed accelerated collagen deposition. The total amount of collagen was similar in both models, but the density appeared greater in the high variability model.

Discussion

Small airways are important to the development of COPD, but difficult to measure—especially in-vivo. This study was designed to 1) show how computational models can simulate complex airway systems and 2) demonstrate how minor changes in the inflammatory response can lead to substantial airway remodelling. These results suggest that tight clustering of immune cells can lead to more rapid and detrimental airway remodelling. In these simulations we use variations in the lung particulate initial condition to encourage immune cell clustering, but more complex dynamics may drive these spatial arrangements. Experimental validation will be required to better validate model results. Future directions include adding more immune cell types and implementing intracellular models to better capture the inflammatory response.