2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(311e) Climate Change Effect over Capacity Expansion Planning for the Power Sector

Authors

The imminent consequences of climate change demand continuous efforts for mitigation and adaptation. Renewable generation is crucial to decarbonizing the power sector, the most significant contributor to carbon emissions [1]. However, growing shares of renewables increase the power system’s exposure to events of low power output. Safeguards like storage and reserve capacity enhance the resilience of power systems, but the significant investment these require demands assertive design methods. Therefore, the challenge arises in decarbonizing our power systems cost-effectively while ensuring reliability.

Additionally, climate change has the dual potential to alter the performance of renewable generation technologies and increase the power demand for cooling, stressing the power system from both the supply and demand sides [2]. It has been demonstrated that climate change will significantly affect renewable generation performance by the end of the century [3]. However, these effects are beyond the lifetime of the components of a power sector, which is between 20 and 35 years. Hence, it is imperative to determine whether climate change scenarios can affect today’s investment decisions.

This work evaluates the optimal configuration of a power system for multiple climate change scenarios. We analyze the individual and combined effects of climate change on the power sector’s demand and generation sides before and after optimizing the power system configuration. Finally, we propose a scenario reduction technique followed by a two-stage stochastic program to determine a power system configuration suitable for all climate change scenarios.

2. Methodology

15 different climate datasets, each spanning one year, individually represent each climate scenario to account for variation between climate models and experiments. The data was collected from 16 different climate models and was classified based on their representation concentration pathways (RCPs): RCP-26, RCP-45, and RCP-85. Each RCP represents a larger climate change effect than the previous one. Each dataset comprises four attributes: solar radiation, wind speed, temperature, and relative humidity. Historical climate data from two sources is also collected as a reference. A statistical analysis between climate scenarios is conducted for three different stages:

2.1. Climate data: As collected from the climate models.

2.2. Demand and renewable generation profiles: Temperature and humidity effects are translated to electricity demand for cooling and heating through degree days. Solar radiation, wind speed and temperature profiles are translated into renewable generation profiles for photovoltaic power (PV), wind turbines (WT), and concentrated solar power (CSP) for predefined technology specifications.

2.3. Power system costs and configuration: Obtained after running a deterministic optimization model with the demand and generation profiles previously calculated.

The power system is designed based on an integrated framework involving a deterministic capacity expansion problem (CEP) with hourly resolution. The linear CEP minimizes the total cost of investment and operation for a power system under fixed annual emission limits and technical constraints. The power system model is integrated with the road transportation sector through electric vehicles (EVs), which introduce additional load but also provide emissions offsetting and increased flexibility via managed charging. Technical constraints, such as reserve requirements and ramping limits, are also incorporated to ensure a reliable system. Investment options include generation, storage, and carbon capture technologies. A detailed formulation of the model can be found elsewhere [4].

Finally, a two-stage decision framework evaluates the power system configuration under selected climate change uncertainty. In this framework, the stochastic programming scenarios are determined such that they cover the entire range of total costs previously calculated. First-stage investment variables are continuous, while second-stage continuous variables represent the operation for each climate scenario, governed by a discrete probability distribution.

3. Case Study

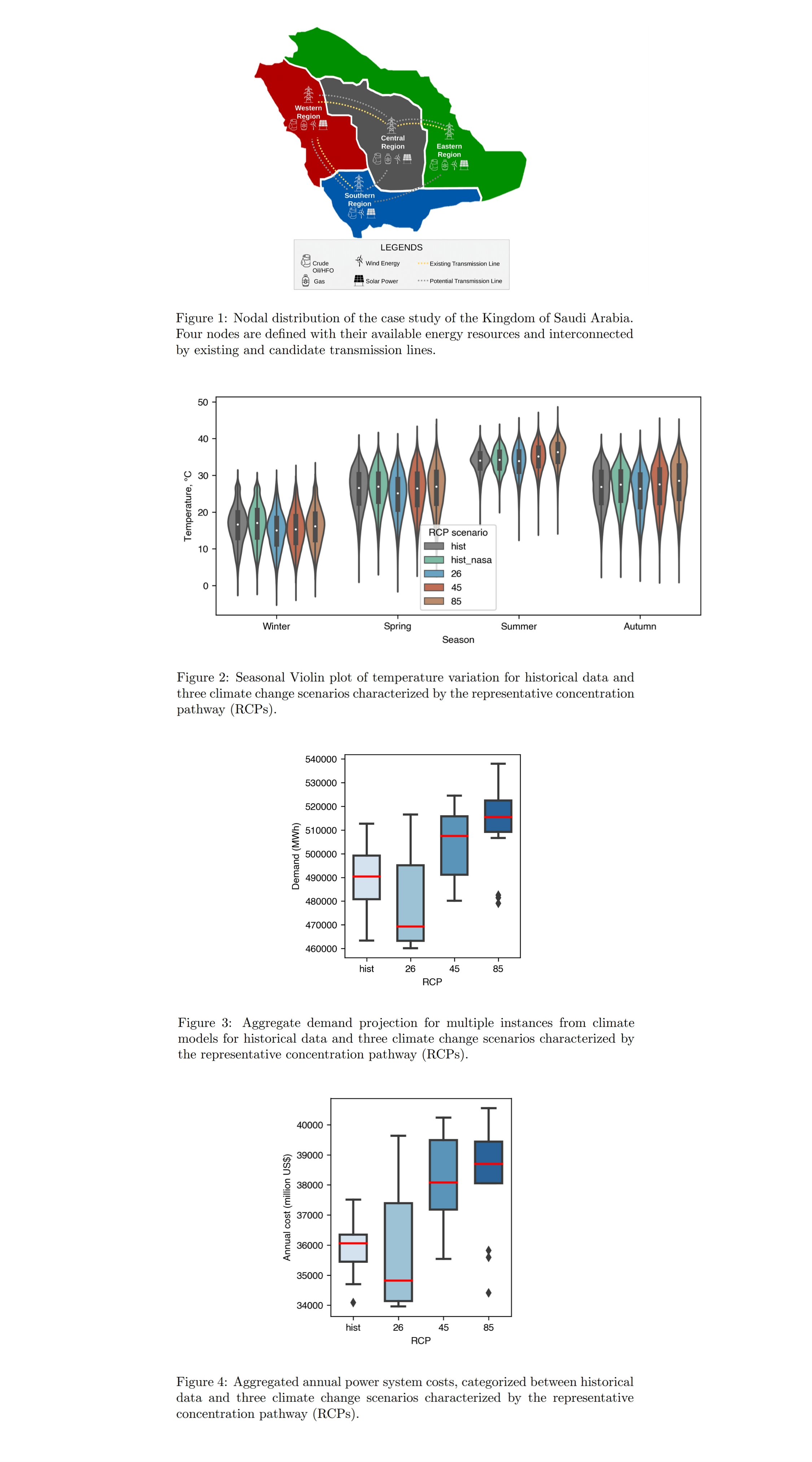

This work focuses on Saudi Arabia’s case study for the year 2050. The country’s desert climate and significant potential for solar power generation make it a prominent case to study the role that climate change can have in redefining its power configuration. The Saudi power system, illustrated in Figure 1, is represented by four nodes, three transmission lines, 8 candidate thermal units (with and without carbon capture), 72 candidate renewable generation units, and eight candidate stationary storage units. We assume that EVs compose 10% of the passenger vehicle fleet, from which 50% incorporate managed charging with vehicle-to-grid technology (V2G).

In all cases, emissions during design are constrained to 100 million ton of carbon dioxide, the model is solved using the extensive formulation, and the resolution of multiple instances of it is done in parallel.

4. Results

A glimpse of the results of the statistical analysis undergone is described below.

4.1. Climate Analysis

Differences between climate scenarios are most evident in the temperature: colder winters and warmer summers are more common with climate change. These effects are most evident for in the maximum summer temperatures (upper tails in summer category in Figure 2). In contrast, the average solar radiation is very similar between climate scenarios. However, all climate scenarios display more days with low solar radiation (cloudy days) during summer than the historical data. This agrees with previous work in this area [2].

4.2. Climate effects on demand and renewable generation

We calculated the total estimated demand required for each climate dataset and compiled the results in Figure 3. As a result of the increasing temperature with climate change, electricity demand for cooling increases considerably with climate scenarios. However, it is also worth noting that the variability between instances for the same climate scenario are very significant. In contrast, the effect of climate change on renewable generation is less evident in aggregated statistics.

4.3. Climate change effects over power system costs and power system configuration

The expected annual costs grow significantly with climate change (Figure 4). There is, however, high variation between instances from the same climate model. Outliers are worth attention, as using a single climate model dataset could result in very misleading cost projections for power systems in as little as 25 years (for the year 2050). Other significant results are listed below:

4.3.1. Overall, the renewable capacity share to achieve the same emission goal can be as low as 15% and as high as 27%.

4.3.2. The renewable capacity and energy needed to decarbonize are more variable with climate change (more uncertainty).

4.3.3. The average generation capacity grows with climate change. For instance, the average total capacity using historical data is 145 GW, whereas it is, on average, 9% larger for RCP-85, the most aggressive climate scenario. However, uncertainty between climate scenarios is considerable.

4.3.4. Generation costs per unit of energy are relatively stable between climate scenarios, ranging between $44/MWh and $54/MWh. This reflects climate change effects are driven mainly by the demand side.

A similar analysis with a fixed demand for all scenarios has helped conclude that demand is the main driver for fluctuations in annual costs. However, variation between optimal power system configurations grows as climate change effects are more prominent. Hence, only considering the impact of demand on the power sector can result in configurations that can mislead policymakers. These findings are the prelude for the two-stage stochastic programming framework, which incorporates multiple climate scenarios, considering the statistical variations that we have noted. The relevance of this statistical analysis and the corresponding scenario reduction strategy will be more evident in out-of-sample simulations. We will demonstrate the potential performance gaps when considering only single climate data instances and the improved performance of the two-stage stochastic program with selected scenarios.

5. Conclusions

This work proposes a methodology to study the effect of climate change on power systems’ capacity expansion planning decisions. Three representative concentration pathways are considered climate scenarios, and 15 climate datasets per climate scenario spanning one year were collected. Additionally, reference historical climate data is also collected from two different sources.

A deterministic capacity expansion model is built to determine investment decisions in generation, storage, and carbon capture technologies for Saudi Arabia’s power sector. The role of carbon capture and EVs is incorporated to attain an integrated perspective. First, a statistical analysis is done over three stages: i) climate data, ii) demand and renewable generation profiles, and iii) power system costs and configurations.

Results from the statistical analysis of climate data demonstrate that significant temperature variation will affect Saudi Arabia’s power sector as early as 2050. On the demand side, higher temperatures can increase the expected average electricity demand by up to 5%. On the generation side, we identify large variability between instances from the same climate scenario. As a result, the renewable share from the optimal power system configuration varies between 15% and 27%. Besides, uncertainty in the optimal renewable share grows with climate change.

Selected climate scenarios will be incorporated in a two-stage stochastic programming framework to determine a configuration with enhanced reliability for the uncertainty caused by climate change. An out-of-sample analysis will be employed as a point of reference to assess the reliability of the configuration obtained.

References

[1] International Energy Agency (IEA), “Carbon Dioxide Emissions in 2022,” tech. rep., 2022.

[2] S. Feron, R. R. Cordero, A. Damiani, and R. B. Jackson, “Climate change extremes and photovoltaic power output,” Nature Sustainability 2020 4:3, vol. 4, pp. 270–276, 11 2020.

[3] A. T. Perera, V. M. Nik, D. Chen, J. L. Scartezzini, and T. Hong, “Quantifying the impacts of climate change and extreme climate events on energy systems,” Nature Energy, vol. 5, pp. 150–159, 2 2020.

[4] D. Fontecha, R. M. Lima, and O. Knio, “Integrated decarbonization using electric vehicles, carbon capture and renewable generation,” tech. rep., King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, 2025.