2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(502c) Case-Based Analysis of Mechanically-Assisted Leaching for Hydrometallurgical Extraction of Critical Metals from Chalcopyrite, Ferronickel Slag, and Ni-MH Black Mass

Authors

The objective of this contribution, whose results were published in the work of Laskar et al. (2024)[1], is to illustrate the simplicity and universality of this mechanically intensified leaching process. Through a comparative analysis of three different case studies, this contribution develops a constructive discussion on the physico-chemical mechanisms that support the attrition-leaching process. The three systems are:

- the mineral aqueous carbonation of ferronickel slags, an industrial waste produced by the New Caledonian pyrometallurgical industry,whose leaching is hindered by the formation of amorphous silica layers [2–4].

- the acid leaching of a chalcopyrite concentrate from the Swedish Aïtik mine, one of the most abundant ores for primary copper production, which is inhibited by complex combined chemical and electronic phenomena [5],

- the dissolution of spent battery black mass powder, prepared at industrial scale from nickel-metal hydride (Ni-MH) automotive batteries, whose particles present a complex superposition of porous oxide layers that are thought to impede dissolution [6].

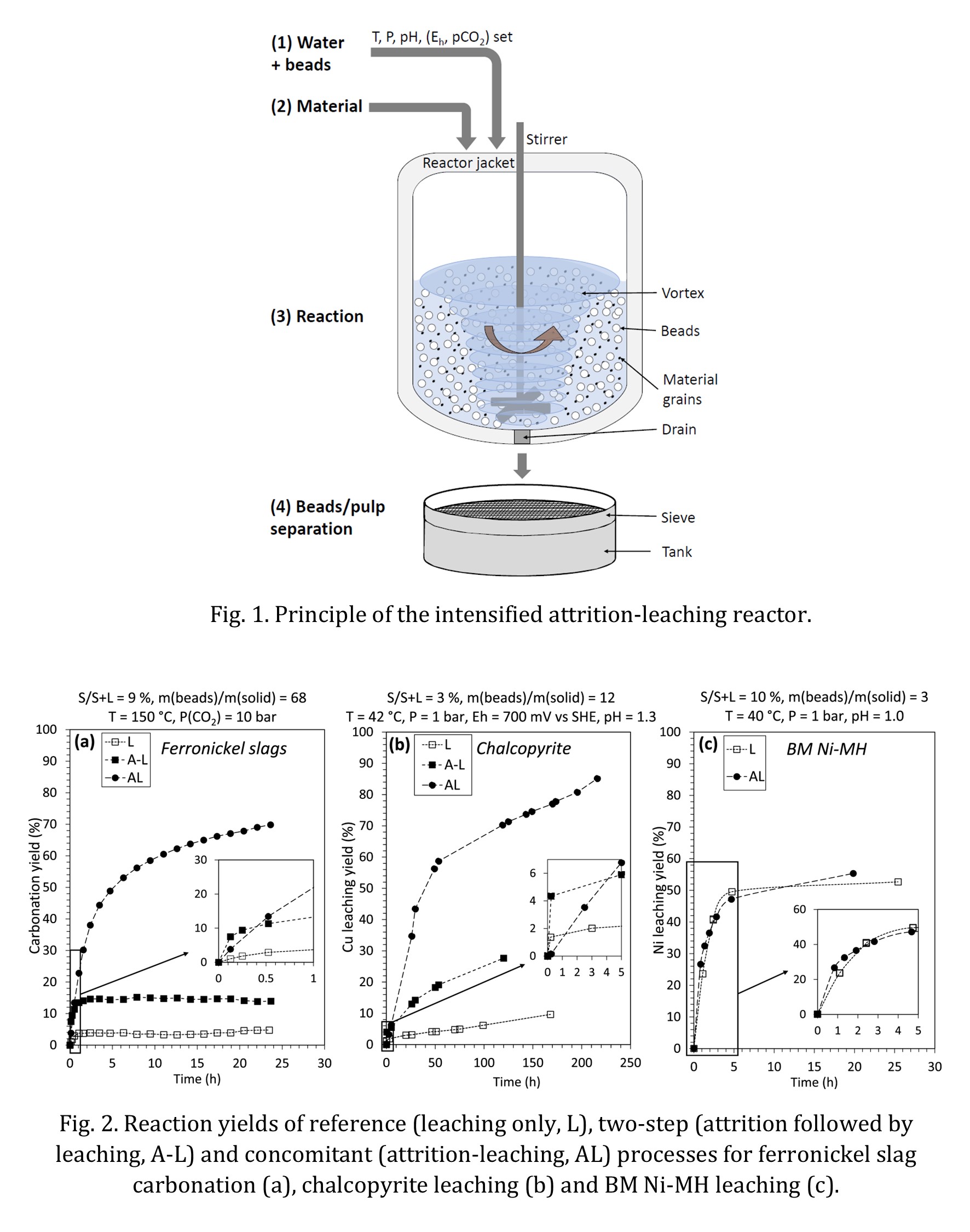

The overall methodology relies on experimental tests carried out in dedicated reactors that allow control of the key process parameters. First, the size distribution and chemical composition of the powder materials were carefully determined. Then, the leaching rate and leaching yield of the material were measured over a fixed period of time, under three different configurations, namely leaching alone, leaching after pre-grinding of the particles, and concurrent attrition and leaching. The size distribution and chemical composition of the residual solids was determined at various times of operation.

More specifically, the carbonation of the nickel slags (composed of MgSi2O5 and Mg2SiO4) was carried out inside a 300 mL reactor, which was essentially the combination of an autoclave and an agitated ball mill, and implemented yttrium-stabilized zirconia grinding beads of 1 mm and an aqueous suspension with 10% by weight of minus 100 μm ferronickel slag. The CO2 partial pressure was varied between 5 and 20 bar, and the temperature in the range 120-180 °C. In this pressurized vessel, the leaching of Mg was followed indirectly by measuring the CO2 consumption resulting of the fast carbonation reaction between Mg2+ and HCO3– aqueous species.

Acid leaching of the chalcopyrite concentrate (composed mainly of a CuFeS2 phase) was carried out in a 6 L reactor at atmospheric pressure, with a suspension at 3.25% by mass in a solution of sulfuric acid. Process parameters were regulated as follows: pH = 1.3, Eh = 700 mV vs. ESH and T = 42°C. Various amounts (from 0.25 to 2 kg) of 1 mm glass beads were introduced into the reactor in order to evaluate the influence of this parameter on the leaching rate, measured by titration of Cu2+ in the aqueous phase.

Finally, the leaching of Ni-MH black mass (composed of a complex mixture of NiO, Ni and LaNi5 particles [7]) was carried out in the same reactor as chalcopyrite, with pH and temperature regulated at 1.0 and 40 °C. The leaching rate was monitored by solution analysis of Ni2+ and La3+ concentrations as well as acid consumption.

Figure 2 provides a first comparison of the leaching performance of the three materials. Under CO2 partial pressure of 10 bar and T = 150°C, 70% of Mg is transformed into carbonates in 24 h, compared with less than 5% for the raw material without attrition and less than 20% for the pre-ground particles (Fig. 2a). The strong effect of the silica beads is also observed in the case of acid leaching of chalcopyrite: the use of 1 kg of glass beads made it possible to achieve a Cu yield of 80% in 200 h, while maintaining a high dissolution rate (Fig. 2b). If these processes operate on distinct time scales due to their difference in intrinsic dissolution kinetics, they both see their extraction yield significantly improved by the combination of leaching and attrition. Conversely, in the case of Ni-MH black mass, no quantitative effect of the attrition-leaching was observed on the time-extraction yield of Ni compared to simple leaching (Fig. 2c).

Analysis of the reaction products using a wide range of analytical techniques sheds light on the mechanisms of action of this coupling for hydrometallurgical processes limited by surface passivation, such as for ferronickel slags and chalcopyrite. In the case of Ni-MH black mass, the porous surface layers that were observed in the initial material do not appear to act as a diffusion barrier. This result allows to show that one of the main Ni-bearing phases contained in the black mass (Ni metal, Ni-La intermetallic or Ni oxide) has a very slow intrinsic dissolution kinetics.

As for particle size distribution, very similar behavior was observed for the three case studies during attrition-leaching tests. Indeed, it was shown that, at an initial stage, grinding of the particles was the dominant process, resulting in a fast particle size reduction. Then, when average particle size reached about 10 µm, attrition took over grinding: the leaching was still very efficient, and the attrition resulted in an increase in very fine particles (0.5–0.7 µm). Concomitant agglomeration phenomena were evidenced, resulting in the presence of two dominant modes (0.9–5 µm) that were stable during most of the process.

As for the chemical characterization of the solid residues (using X-ray diffraction, SEM-EDX local analysis, elemental analysis), one of the major result, common to all three cases, is that the phases resulting from the chemical reactions were in very good agreement with thermodynamic equilibrium calculations reproducing the experimental conditions. This means that, while the initial systems could be strongly impeded by mass transport limitations, the continuous refreshing of the active surface implemented in the attrition-leaching reactor allowed the chemical reactions to reach thermodynamic equilibria. As a consequence, thermodynamic calculations were used to explore the influence of process parameters and helped to choose the most appropriate conditions depending on each specific chemistry.

References

[1] C. Laskar, A. Dakkoune, C. Julcour, F. Bourgeois, B. Biscans, L. Cassayre, Case-based analysis of mechanically-assisted leaching for hydrometallurgical extraction of critical metals from ores and wastes: application in chalcopyrite, ferronickel slag, and Ni-MH black mass, Comptes Rendus. Chimie 27 (2024) 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5802/crchim.325.

[2] A. Dufourny, C. Julcour, J. Esvan, L. Cassayre, P. Laniesse, F. Bourgeois, Observation of the depassivation effect of attrition on magnesium silicates’ direct aqueous carbonation products, Front. Clim. 4 (2022) 946735. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2022.946735.

[3] C. Julcour, L. Cassayre, I. Benhamed, J. Diouani, F. Bourgeois, Insights Into Nickel Slag Carbonation in a Stirred Bead Mill, Front. Chem. Eng. 2:588579 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3389/fceng.2020.588579.

[4] G. Rim, D. Wang, M. Rayson, G. Brent, A.-H.A. Park, Investigation on Abrasion versus Fragmentation of the Si-rich Passivation Layer for Enhanced Carbon Mineralization via CO2 Partial Pressure Swing, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59 (2020) 6517–6531. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.9b07050.

[5] A. Dakkoune, F. Bourgeois, A. Po, C. Joulian, A. Hubau, S. Touzé, C. Julcour, A.-G. Guezennec, L. Cassayre, Hydrometallurgical Processing of Chalcopyrite by Attrition-Aided Leaching, ACS Eng. Au (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsengineeringau.2c00051.

[6] M. Zielinski, L. Cassayre, P. Destrac, N. Coppey, G. Garin, B. Biscans, Leaching Mechanisms of Industrial Powders of Spent Nickel Metal Hydride Batteries in a Pilot-Scale Reactor, ChemSusChem 13 (2020) 616–628. https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201902640.

[7] M. Zielinski, L. Cassayre, P. Floquet, M. Macouin, P. Destrac, N. Coppey, C. Foulet, B. Biscans, A multi-analytical methodology for the characterization of industrial samples of spent Ni-MH battery powders, Waste Management 118 (2020) 677–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2020.09.017.