2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(234a) Carat: A Framework for Carbon Atom Tracing in Chemical Value Chains Via Chemistry Language Models

Authors

The chemical industry is increasingly prioritizing sustainability, with a strong focus on reducing its carbon footprint and moving toward net-zero targets. By 2026, the Together for Sustainability (TfS) consortium will mandate the reporting of biogenic carbon content (BCC) in chemical products [1], posing a significant challenge for the industry. In this context, CarAT (an automated, scalable “Carbon Atom Tracing” methodology) offers a practical way to dynamically calculate and report BCC across industrial value chains. Many chemical manufacturers use Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems to manage procurement, manufacturing, logistics, and sales data [2], but these systems lack the molecular-level detail required to differentiate fossil and biogenic carbon sources within a product.

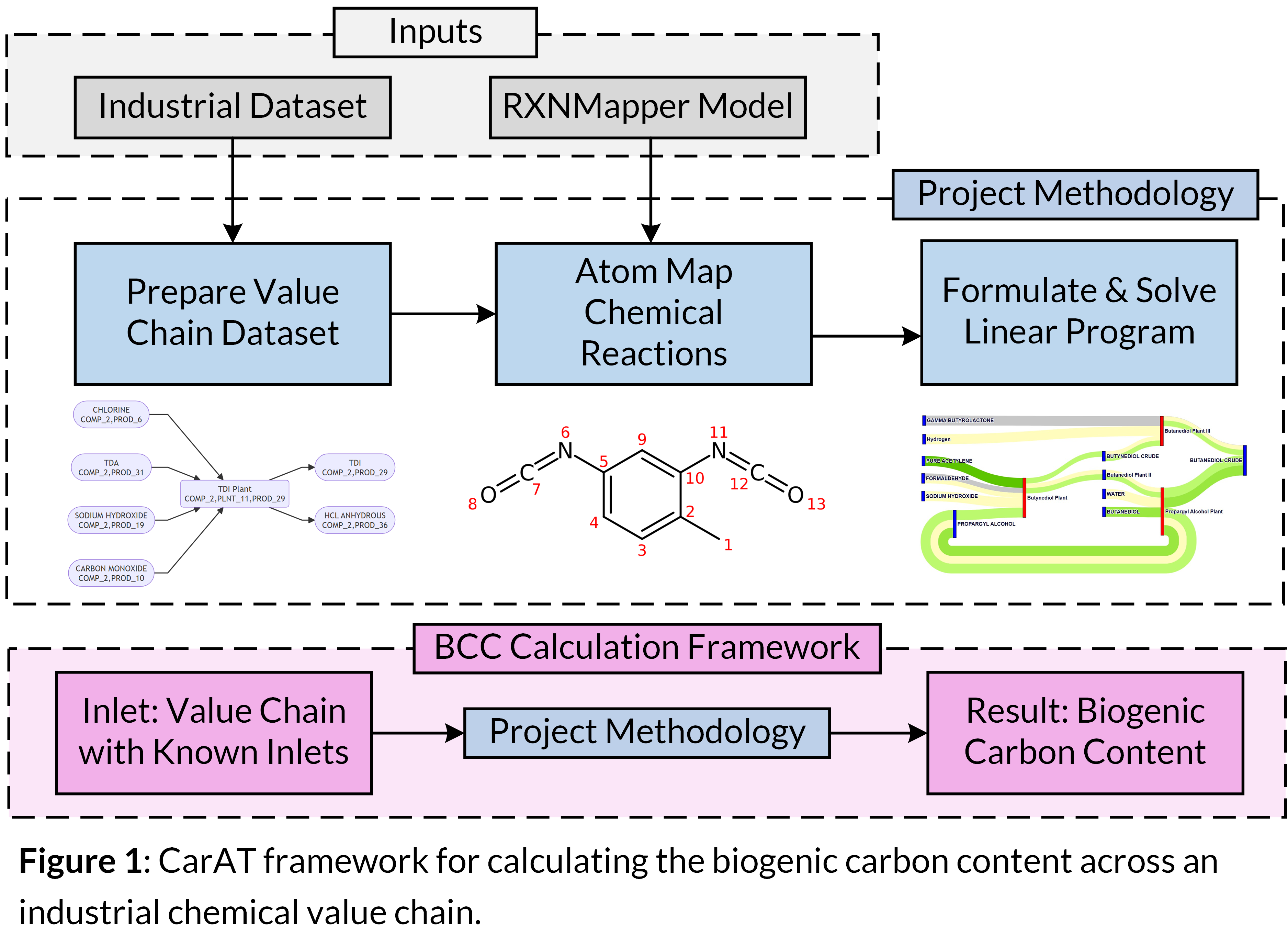

In the chemical sector, a value chain can be considered an interconnected network of raw materials, production processes, and final products, or a series of value-adding chemical reactions and transformations that convert feedstocks into high-value products [3]. Calculating BCC across these networks is difficult, because it depends on factors such as feedstock composition, process efficiency, and various operational variables. CarAT bridges the gap between high-level ERP data and the molecular detail needed for accurate BCC reporting. Our method leverages a pre-trained transformer model (RXNMapper) to automate atom mapping across reactions. A generalisable linear program then propagates BCC across the value chain, ensuring consistent tracking through loops and mixed feedstocks.

CarAT Framework Overview

CarAT consists of three stages:

1. Data Preparation and Value Chain Representation: The value chain is represented as a bipartite, directed graph in which “mix” nodes consolidate feedstocks or recycled streams, and “production” nodes describe transformations at chemical facilities. This structured approach links ERP-level material flows with the actual chemical species involved.

2. Language-Model-Driven Atom Mapping: To link inlet carbon atoms to outlet products, CarAT employs IBM’s RXNMapper model [4], a transformer-based machine learning algorithm that infers atom-to-atom mapping by analyzing reaction SMILES [5]. This step identifies the fraction of carbon atoms in each product that originate from each reactant, creating a “bill of atoms.” Automation at this stage significantly reduces manual effort, especially for large and complex reaction networks.

3. Linear Program (LP) Optimization for BCC Calculation: The linear program ensures that carbon attribute shares (for instance, biogenic vs. fossil) are tracked consistently across all nodes, including those with recycle loops. Each node’s outputs inherit carbon attributes from its inputs, and the constraints enforce an atom or mass balance. By summing these shares, the final BCC is computed for every product, providing a dynamic snapshot of biogenic vs. fossil carbon in each material.

Validation with an Industrial Toluene Diisocyanate (TDI) Value Chain

CarAT was applied to a 40-node industrial TDI value chain under three scenarios:

• Base Case (All Fossil Feedstocks): Fossil-derived inputs yield TDI with zero biogenic content, confirming the baseline correctness of the method.

• Renewable Feedstock Scenario: Substituting natural gas with a 100 percent biogenic source shifts part of the carbon flow from fossil to renewable, yielding a final TDI product with approximately 22 percent biogenic carbon. This showcases CarAT’s ability to track mixed carbon sources accurately.

• Butanediol Value Chain with a Recycle Loop: In a separate butanediol process that includes a recycle stream, CarAT handles looped pathways, demonstrating that partial biogenic inputs lead to traceable fractions of renewable carbon in the final product.

In all cases, the linear program converges to a solution that accurately allocates carbon attributes across multiple nodes and materials, confirming CarAT’s robustness and generalizability.

Significance and Future Directions

CarAT’s principal contribution is its automated, scalable approach for BCC calculation in complex industrial value chains. This method enables dynamic updates whenever feedstock composition or process parameters change, and it directly supports the upcoming TfS requirements for BCC reporting. By capturing atom-level transformations, CarAT also provides strategic insights into how altering feedstock composition affects the biogenic fraction of downstream products.

Future work includes adapting the RXNMapper model for specific reaction classes, extending the linear program to trace other elements (for example, nitrogen), and developing an inverse optimization capability that would allow manufacturers to specify a target BCC and solve for the feedstock composition that meets that target. By merging ERP data, advanced atom mapping, and linear optimization, CarAT offers a forward-looking solution to the chemical industry’s growing need for transparent and adaptable sustainability reporting.

References

[1] Together for Sustainability (TfS) (2024) TfS Product Carbon Footprint Guideline 2024. Available at: https://www.tfs-initiative.com/app/uploads/2024/12/TfS-PCF-Guidelines-2024.pdf (Accessed: 4 April 2025).

[2] Gupta, M. and Kohli, A. (2006) ‘Enterprise resource planning systems and its implications for operations function’, Technovation, 26(5), pp. 687–696. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2004.10.005.

[3] De Backer, K. and Miroudot, S. (2014) Mapping Global Value Chains, SSRN Scholarly Paper 2436411. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2436411 (Accessed: 4 April 2025).

[4] Schwaller, P., Hoover, B., Reymond, J.-L., Strobelt, H. and Laino, T. (2021) ‘Extraction of organic chemistry grammar from unsupervised learning of chemical reactions’, Science Advances, 7(15), p. eabe4166. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe4166.

[5] Weininger, D. (1988) ‘SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules’, Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences, 28(1), pp. 31–36. doi: 10.1021/ci00057a005.