2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(394f) A Benchmark Simulation Model of Green Ammonia Production for the Development of Process Safety and Monitoring Approaches

Authors

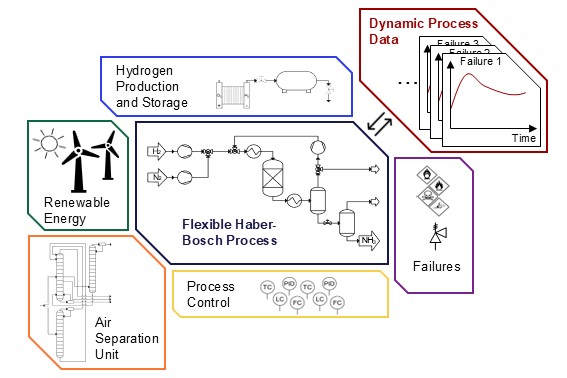

Besides reservations regarding high electricity demands and prices, the electrification of the chemical process industry requires another significant adaptation. Renewable energy is produced from primarily fluctuating sources, which starkly contrasts the traditionally continuous operation of chemical processes at a steady state. This is particularly true for processes for which the highly fluctuating renewable electricity supply directly influences feedstock production. Ammonia produced from green hydrogen is the perfect example.

Literature shows that water electrolyzers producing green hydrogen can rapidly adjust their loads to accommodate changes in electricity supply [2]. The same applies to air separation units that produce nitrogen, the second feedstock for ammonia production [3]. Conversely, ammonia is typically produced in the Haber-Bosch (HB) process, which is operated at a steady state. This contrast can be mitigated by introducing large buffer tanks for the reactants. Due to the high cost of hydrogen storage, several studies advocate for a flexible operation of the HB process, enabling it to adapt to varying hydrogen supplies. In our work, we focus on an HB process with extended flexibility, allowing for 30-130% of its nominal production capacity, which significantly decreases the required capacity for hydrogen storage.

Despite potential economic gains, higher flexibility in operation challenges process control and safety methods, such as process monitoring and fault detection. The constantly changing process conditions resulting from different feed flow rates and varying optimal operating conditions can mask process and equipment failures, and failures can lead to potentially risky process conditions and loss of control. Thus, effective monitoring and control of the process is essential, especially in processes involving flammable substances at high temperatures and pressures, such as in the HB process. In conclusion, the flexible operation of HB plants complicates both process control and failure detection.

We introduce a new benchmark simulation model for the hydrogen economy, including a dynamic failure dataset. Our definition of failure is always related to a piece of process equipment that behaves abnormally, for example, valves, compressors, or sensors. Equipment failures can alter process conditions, leading to a new stable operating point or causing the system to run away, necessitating blow-offs or shutdowns. While failures resulting in new stable operating points are challenging to detect, a potential loss of control introduces significant risks to the environment and human life. We provide detailed failure descriptions and the belonging time-series data, addressing scenarios in both groups. The benchmark model can be used to simulate the renewable HB plant dynamically, while the dynamic process data can be used in risk monitoring or fault detection studies. By addressing a sustainable and emerging process as part of the hydrogen economy, we are confident that our ammonia benchmark simulation model contributes to the development of new process control and monitoring approaches, thereby enhancing process safety.

[1] D. R. MacFarlane et al., “A Roadmap to the Ammonia Economy,” Joule, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 1186–1205, Jun. 2020, doi: 10.1016/J.JOULE.2020.04.004.

[2] J. Armijo and C. Philibert, “Flexible production of green hydrogen and ammonia from variable solar and wind energy: Case study of Chile and Argentina,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 1541–1558, Jan. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.11.028.

[3] C. Tsay, A. Kumar, J. Flores-Cerrillo, and M. Baldea, “Optimal demand response scheduling of an industrial air separation unit using data-driven dynamic models,” Computers & Chemical Engineering, vol. 126, pp. 22–34, Jul. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.compchemeng.2019.03.022.