2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(189u) Aerosol Synthesis of Flame Formed Carbon Nano Onions Embedded with Reduced Titania: Insights into Morphological and Optical Features

The global energy crisis and environmental pollution are the main challenges of recent times due to the enormous rise in world population. The research community is striving to find sustainable solutions to address the energy demand and environmental remediation. Among various approaches, the light driven techniques such as photocatalysis, photochemical and photo sensing have emerged as promising methodologies. These approaches provide sustainable solutions as they can harness visible and solar light for different applications such as water splitting, wastewater treatment, air purification, environmental monitoring, and advanced optoelectronic processes. Researchers have synthesized and tuned the properties of numerous metal and non-metal-based photoactive materials for these applications. However, the performance of these materials is compromised owing to their inefficient visible light absorption and poor charge carrier dynamics. Recently, carbon nano onions (CNOs) have attracted the attention of researchers owing to their unique structural and size-dependent photoluminescence features that significantly enhance charge carrier capacity and visible light absorption (Tripathi et al., 2017). The quantum confinement behavior of carbon nano-onions (CNOs) arises from their concentric graphitic structural layers. This unique carbon morphology also promotes their optical absorption features (Aggarwal et al., 2023). Doping CNOs with metal oxides can induce defects in the structures, further improving their surface reactivity and functionality due to synergistic effects. The aim of this study is to synthesize flame-formed CNOs embedded with reduced titania via flame spray pyrolysis and investigate the impact of titania addition on morphological and optical features of the CNOs. Incorporation of titania can modify the nucleation to agglomerate stages involved in CNOs formation, leading to improved morphology with enhanced optical absorption in the visible region. The optical band gap of these CNO composites is wider than the pristine CNOs, making them excellent material for different photocatalytic, photo-sensing, and photochemical applications.

Materials and Methods:

Xylene and titanium isoproproxide solution was used as a precursor for the synthesis of composite material by flame spray pyrolysis. The detailed experimental setup has been explained in our previous work (Tanveer et al. 2025). O₂ and CH₄ were used for the FSP flamelet, and their respective ratio was maintained at 2. The solution was injected into the reactor at a feed rate of 0.5 mL/min using perlistic pump. The feed rate was maintained, ensuring the same synthesis conditions throughout the experiment. A mixture of oxygen and nitrogen was used as a dispersion medium for the atomization of the precursor solution through an annular aperture around a capillary tube. Atomized precursor droplets are encountered with flamelet at the nozzle and ignited, followed by evaporation and a shift into the gas phase. Nitrogen-diluted dispersion oxygen gas ensures the controlled combustion of the precursor. Moreover, nitrogen was used as sheath gas, leading to quenching of flame. The entrainment of surrounding air can alter the flame combustion, so the flame is confined inside a quartz tube to ensure fully controlled synthesis conditions. The precursor was combusted at an equivalence ratio of 2.5 and with varying TTIP concentration to ensure 0.5 % to 5 wt% of TiO₂ in the final product. As formed, carbon nanocomposites were collected on the glass fiber filter with the help of a high-pressure vacuum pump. The collected nanostructures consist of organic carbon and unburned residues, which were removed with the Soxhlet extraction method. Following this, as obtained black CNO composites were pyrolyzed in a tube furnace at 500 °C for 3 h under a nitrogen environment, which significantly improve the graphitic structures.

Characterization Techniques:

The morphology and particle size of CNOs and respective composites were analyzed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM-2100F, Jeol Inc.). Raman spectroscopy analysis (Thermo DXR2xi Raman) of the as-synthesized nanostructures was performed using a green laser at wavelength λ = 532 nm and a 50x objective with a 50 µ confocal pinhole aperture. The laser power was maintained at 1 mV for an exposure time of 0.50 sec and 100 scans. The surface functional groups of CNOs and their composites were analyzed with FTIR using a Thermo Nicolet iS50 model (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Madison, USA). The spectra were recorded in iS-ATR mode from 400 to 4000 cm⁻¹ at variable scans for optimum spectra. Optical features of the CNOs and composites were measured using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Shimazdu). For this purpose, the sample was injected in a quartz cuvette with a path length of 1 cm and a wavelength range of 300–2500 nm. Based on the absorption spectrum, the band gap of the samples was measured using the Tauc plot method. OC/EC and EC4–6/EC1–3 ratios were measured using a thermal-optical carbon analyzer (Lab OC-EC Aerosol Analyzer, Sunset Laboratory Inc.) applying high-temperature protocol NIOSH870.

Results and Discussion:

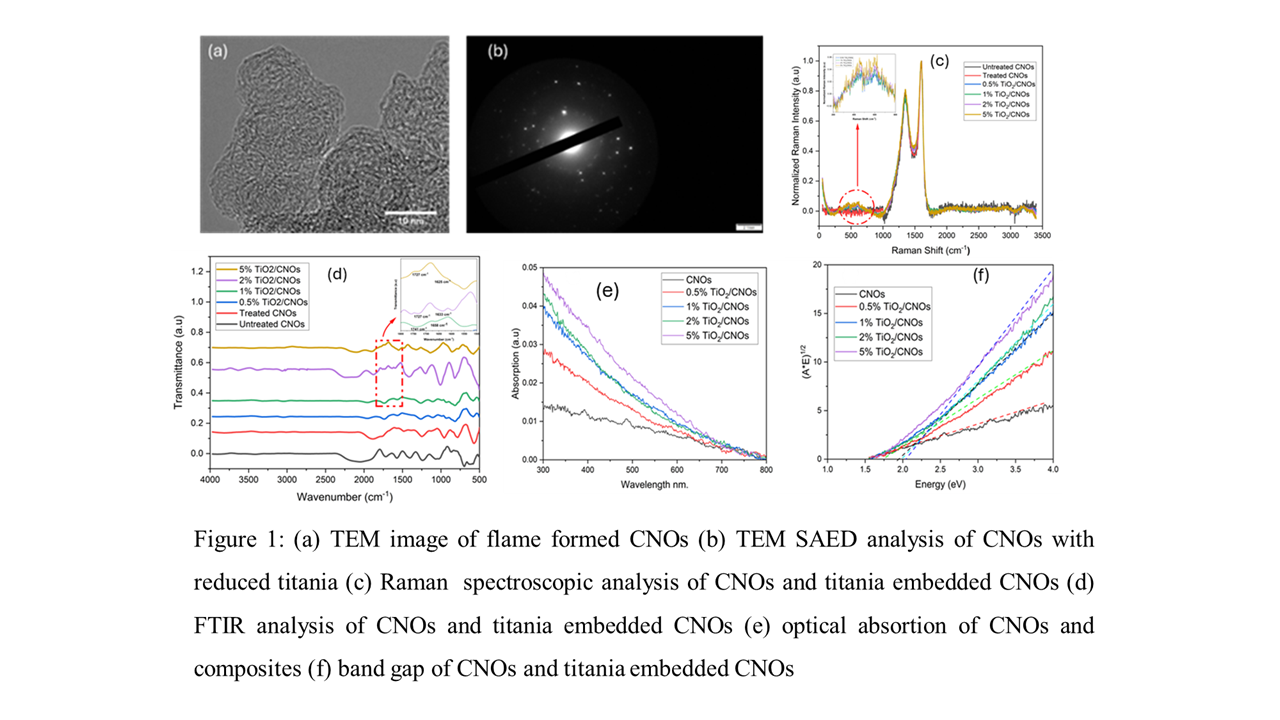

TEM results show that CNOs exhibit concentric graphitic layered structures (Figure 1a). These spherical CNOs are loosely agglomerated due to high temperature and particle number concentrations obtained in the closed FSP system, which restricts the entrainment of air and increases the residence time of carbon nanoparticles at high temperature. These conditions are also shown to increase the fraction of elemental carbon (EC) formed in the process, leading to an increase in the graphitization of CNO composites (Tanveer et al., 2025). The size of these CNOs ranges from 4.3 nm to 27.4 nm, with a mean diameter of 10.18 nm. Thermal optical carbon analysis and TGA analysis show that treated CNOs contain fewer OC fractions, resulting in the elimination of highly disordered carbon that can cause aggregation and the formation of large particles and agglomerates (Tanveer et al., 2025). Also, the presence of higher fractions of EC4-6 induces turbostratic stacking and restricts excessive particle growth. Similarly, the particle size of the TiO₂-embedded CNOs ranges from 5.1 nm to 57.1 nm with a mean diameter of 12.93 nm. The increase in particle size is owing to the presence of comparatively large TiO2 particles. TEM diffraction of the TiO2 show absence of the strong diffraction rings which suggests that mixed-phase TiO₂ is formed (Figure 1b). This is attributed to the lean oxygen environment synthesis conditions, which result in incomplete oxidation of TTIP and formation of reduced titania species. Raman spectroscopy results demonstrated that defects to the graphitic ID/IG ratio drop from 0.79 to 0.75 (Figure 1c). This is attributed to the fact that most of the PAHs and oxygenated organics, which contribute to disorder in CNOs and impart the Sp3 bonded defects, are primarily removed through the extraction process. Moreover, thermal treatment transforms the amorphous carbon into more ordered and graphitic forms of carbon. Raman spectroscopic results of 0.5% TiO₂/CNOs to 5% TiO₂/CNOs exhibit two small peaks at 455 cm⁻¹ and 601 cm⁻¹, typically associated with the rutile phase. Normally, Raman spectroscopy shows a peak at 144 cm⁻¹ for the anatase phase, but here no peak appears at this location (Mazza et al., 2007). This shows that as-produced titania species are mostly rutile in nature with reduced oxygen vacancies resulting in an increase of defects to the graphitic nature of the CNOs. Raman analysis of TiO₂-embedded CNOs shows that as TiO₂ concentration is raised from 0.5% to 5%, the ID/IG ratio increases from 0.76 to 0.82. Also, the introduction of titania also contributes to the catalytic oxidation of OC fractions and restricts their conversion into graphitic EC fractions, leading to an enhanced defect-induced structure of composites. FTIR analysis (Figure 1d) further confirms the crucial role of carboxylic and carbonyl functional groups in enhancing the reactivity of the CNO composites. Moreover, results show that in TiO₂/CNOs composites, the interaction between titania species and different functional groups on the CNOs surface results in the formation of Ti-OH, Ti-O-C, and Ti-O-Ti functionalities. The bending vibration of adsorbed hydroxyl groups on the titania surface leads to the formation of a Ti-OH bond between 1625 cm⁻¹ and 1658 cm⁻¹ (Verma et al., 2017). The peaks between regions 1000 cm⁻¹ and 500 cm⁻¹ are typically associated with the Ti-O-C and Ti-O-Ti. The peak around 800 cm⁻¹ confirms that surface hydroxyl groups on the surface of TiO₂ interact with residual aromatics and carboxylic acid groups and form the Ti-O-C bonds. While the transmittance peaks between 400 cm⁻¹ and 700 cm⁻¹ are typically associated with the formation of TiO₂ and Ti-O-Ti bonds. The presence of Ti-O-C bonds confirms that there is strong linkage between titania and CNOs. The peaks related to the carbonyl functional group are present between 1727 cm⁻¹ and 1741 cm⁻¹, while the region between 1100 cm⁻¹ and 1300 cm⁻¹ exhibits peaks associated with C-O. Results also demonstrate that CNO composite material has higher absorption in the visible region. Oxygen-deficient and high-temperature conditions also restrict the complete oxidation of the TTIP, resulting in the formation of mixed phases of TiO₂ with oxygen vacancies (X. Pan et al. 2013). This was confirmed by the SAED analysis showing the absence of typical diffraction pattern of TiO₂ (Figure 1b). With an increase in TiO₂ concentration, the shift from the red to the blue region is observed (Figure 1e). Moreover, band gap of pure CNOs is 1.5 eV (M. Tanveer, et al. 2025), and it is shifted up to 2.04 eV when the concentration of TiO2 is increased to 5 wt-% (Figure 1f). This shows that presence of small amount of TiO2 induces synergistic effects and improves the absorption of as produced composite material. Therefore, the enhanced structural composition of TiO2-embedded CNO composites, leading to better optical absorption, renders them highly promising for photocatalytic and photochemical applications.

Conclusion:

Flame formed CNOs embedded with reduced titania were synthesized through closed FSP system that provides oxygen deficient and entrainment air restricted environment. This results in formation of EC rich CNOs with graphitic structure. These EC fractions are formed by the polymerization and condensation process of PAHs present in the form of OC fractions. However, introduction of titania species leads to oxidation of OC fractions and thereby reduces the transformation process from OC to EC. This controlled growth of ECs shifts the optical absorption of CNOs from infrared to visible region making it an excellent photocatalyst for the visible light driven photocatalytic and photochemical applications.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by UEF doctoral school and JAES grant (Versa-MOF 6833-57e45).

References:

- Ji, et al. (2021). Ultrason. Sonochem.74, 1350-4177.

M.Tanveer, et al., (2025) Aerosol Sci. Tech. 59, 343-356.

- Pan, et al., (2013) Nanoscale, 5, 3601

Tripathi. K et al. (2017) ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5, 3982- 3992.

Verma, R et al. (2017) RSC Adv. 70, 44199–44224

Aggarwal R et al. (2023) Carbon. 208, 436-442.

Maaz T et.al. (2007) Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. 5, 045416