2025 AIChE Annual Meeting

(63i) Active Brownian Particles: Obtaining and Interpreting Effective Interactions

Authors

Passive particles merely undergo Brownian motion, whilst active particles have some energy source to power additional motion. Many biological systems, such as schools of fish and flocks of birds, can be modelled as active particles, with active Brownian particles (ABPs) being one model choice. Such models can offer insight into these systems’ structural and dynamic behaviour. Here, we present an approach to obtain effective pair potentials which describe the structure of two-dimensional systems of ABPs.

The particle arrangements are obtained from active molecular dynamics simulation. The effective pair potential, ueff(r), is found by an inverse method, which matches the radial distribution function, g(r), found from two different methods: the traditional distance–histogram and a newer test-particle insertion method [1]. The inverse method has been previously demonstrated to work efficiently with simulated equilibrium configurations of passive particles [2]. We have now applied the method to active particle structures.

Interestingly, although active particles are inherently not in equilibrium, we can still obtain effective interaction potentials which accurately describe the structure of the active system. Furthermore, treating these potentials as equilibrium ones allows us to measure the effective chemical potentials and pressures. Effective pair potentials are found for a variety of passive interactions, Péclet numbers (ratio of active to passive motion) and densities. Both the passive interactions and active motion of the active Brownian particles contribute to their effective interaction potentials.

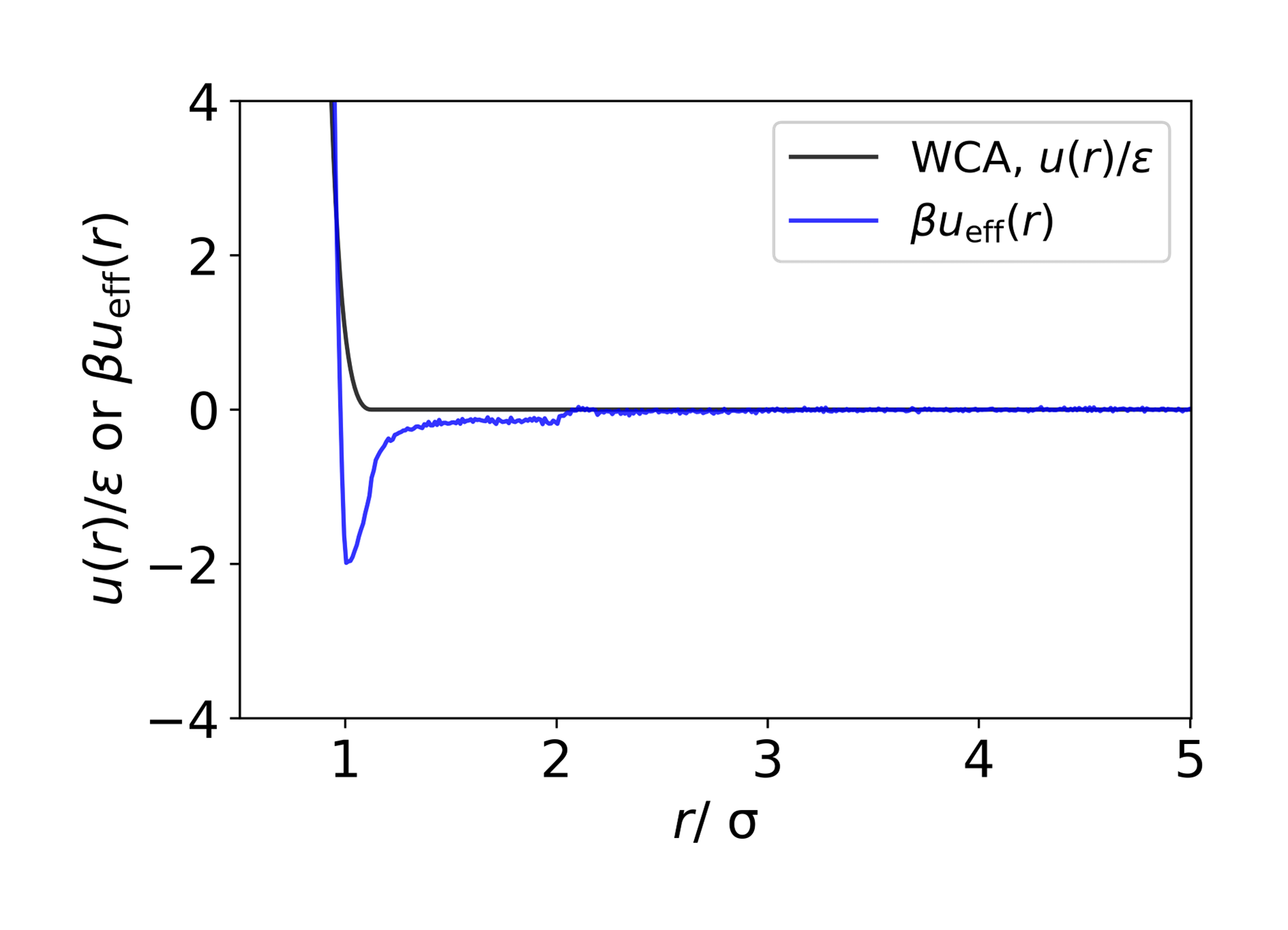

Purely repulsive passive interactions give particularly insightful effective pair potentials, since these contain attractive wells (see Figure 1): this is a clear demonstration of the emergent attractive behaviour of ABPs. Furthermore, the shape, such as the depth, of these attractive wells offers a means to quantify this emergent behaviour. The density-dependence of ueff(r) quantifies the many-body effects of ABPs. We conclude that we can learn about non-equilibrium systems through methods designed for better-understood equilibrium systems.

Figure 1. Effective interaction potential for active particles (blue line) compared with the underlying passive Weeks–Chandler–Anderson (WCA) potential (black line). Distances are scaled by the particle diameter, σ, and energies by or the thermal energy ( ).

References

[1] J. Chem. Phys. 2025, 162, 074103.