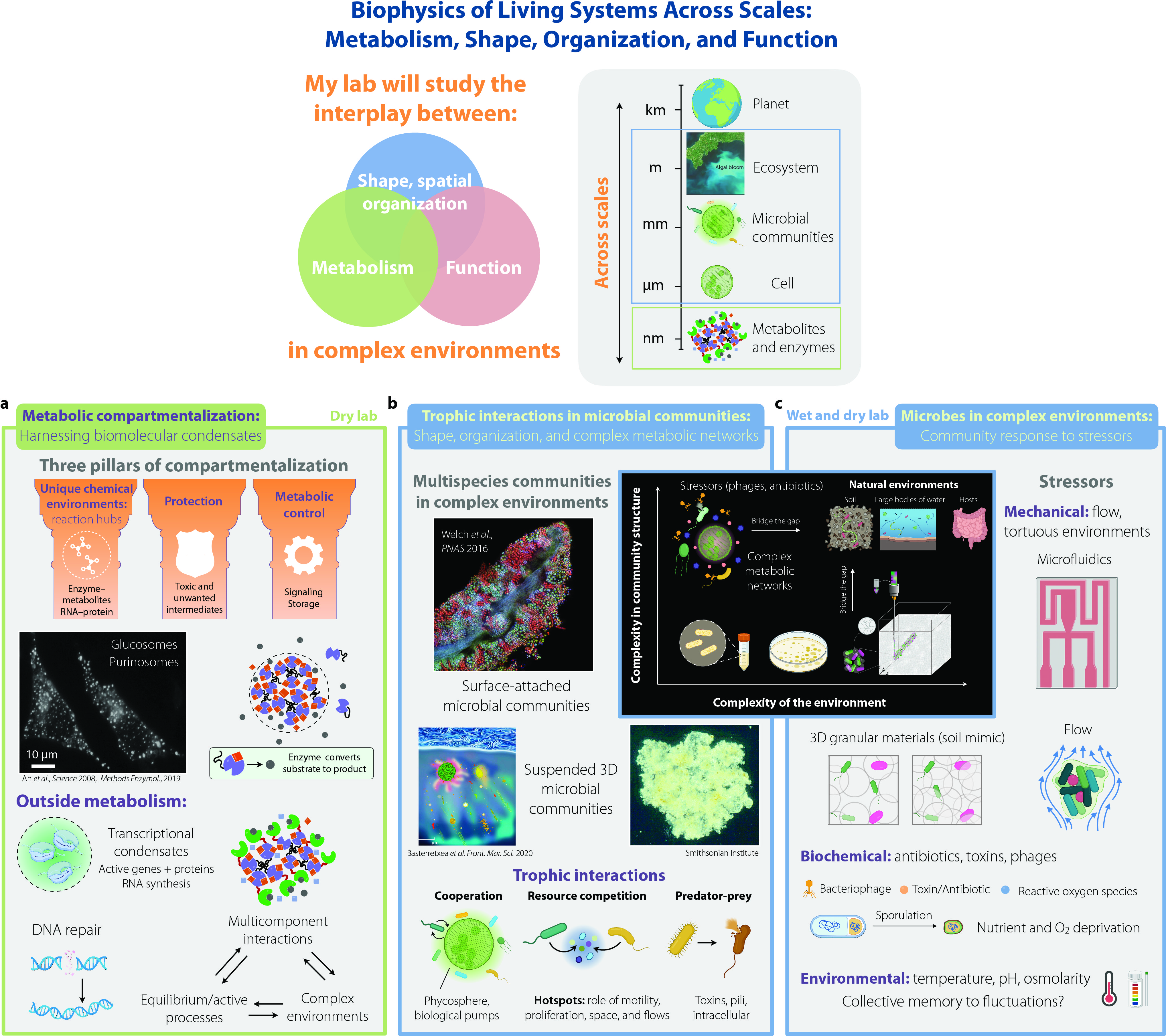

Research direction 2. Trophic interactions in multispecies microbial communities: Shape, organization, and complex metabolic networks. Wet and dry lab.

Microorganisms typically do not live in isolation but form spatially structured multicellular communities composed of multiple species and heritable phenotypes. This spatial arrangement plays a pivotal role in influencing various biological functions, including community growth, stability, metabolite cross-feeding, and diversity. Examples include microbial colonies in soils, hosts, and large bodies of water, where trophic interactions between different bacterial species, as well as interactions with plants and phytoplankton, strongly influence carbon and nutrient cycling and food webs. Laboratory studies often focus on these microbial systems in well-mixed cultures or single-species surface-attached colonies, providing valuable insights into cellular processes but failing to capture the spatial arrangement of different cell types found in nature. To address this gap in knowledge, our lab will study the interplay between different microbial metabolic interactions, colony shape, collective behavior, and spatiotemporal organization of 2D and 3D multispecies communities in complex settings that mimic their natural environments (Fig. 2b).

To achieve this goal, we will conduct experiments to visualize real-time trophic and metabolic interactions among microbes in multispecies communities in complex environments. These interactions will include mutualistic relationships (e.g., bacteria-cyanobacteria/phytoplankton), resource competition (different bacterial species competing for the same resource), and predator-prey dynamics (e.g., myxobacteria/bdellovibrio-bacteria). To understand how these interactions influence spatiotemporal organization, collective behaviors, and colony shape, we will employ crowded environments, live imaging, metabolomics, and biophysical modeling. I anticipate that the outcomes of this new direction will extend beyond prior research and shed light on the spatial diversity and organization of multicellular and multispecies structures in real-life environments, thus bridging the gap between nature and lab experiments.

Research direction 3. Microbes in complex environments: Community response to stressors. Wet and dry lab.

In nature, bacteria face multiple challenges, from fluctuating environments, mechanical stresses, tortuous environments, and nutrient deprivation to chemical and biological stressors like antibiotics, reactive oxygen species, or bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria). The impact of such stressors on bacteria has been often explored using continuously mixed liquid cultures. However, bacteria face these situations in structured and extended environments, such as hosts, soils, and aquatic settings, where the cells can collectively self-organize into spatially structured communities. Despite the pivotal influence of bacterial spatial organization on diverse biological functions, how such organization is influenced by, and in turn influences, interactions with stressors remains poorly understood. These interactions are of fundamental interest in biology, ecology, and physics, and have critical implications for biogeochemistry, the environment, food, health, and industry.

To address this gap in knowledge, our aim is to unravel how microbes collectively respond to biochemical and mechanical stressors, and how this response interacts with colony shape, spatial organization, and function. To this end, we will conduct experiments exposing bacteria and cyanobacteria to various stressors in complex, crowded environments, combined with biophysical modeling. I anticipate that exploring these questions will illuminate how microbial communities adapt to fluctuating environments and stressors, thereby bridging the gap between laboratory studies and natural microbial habitats (Fig. 2c). This research direction combined with 2 will also establish a framework for controlling and engineering microbial communities according to specific needs.

Summary: My research program seeks to advance our understanding of how living matter self-organizes and functions in complex settings that mimic real-life environments. To address this overarching research direction, my lab will combine experiments and theoretical modeling. The main goal of this fully integrated approach is to understand the fundamental biophysical principles underlying self-organization and function of living systems in real-life environments, and elucidate the coupling and feedback loops between morphology, function, physiology, and stressors.

The overall development and outcome of this research plan will be greater than the sum of its parts. For instance, research directions 2 and 3 will feed each other naturally. In addition, the theoretical approaches that we will develop to tackle the questions proposed in research direction 1 will certainly inform and help to develop theoretical approaches in research directions 2 and 3. Finally, this research plan will provide opportunities to establish fruitful collaborations with multiple groups in Chemical and Biological Engineering departments, as well as in Physics, Microbiology, Applied Mathematics, Materials, and Chemistry departments.