Breadcrumb

- Home

- Publications

- Proceedings

- 2024 AIChE Annual Meeting

- Materials Engineering and Sciences Division

- Excellence in Graduate Student Research

- (272b) Novel Chemi-Mechanical Recycling Process to Purify and Blend Co-Mingled Polyolefins

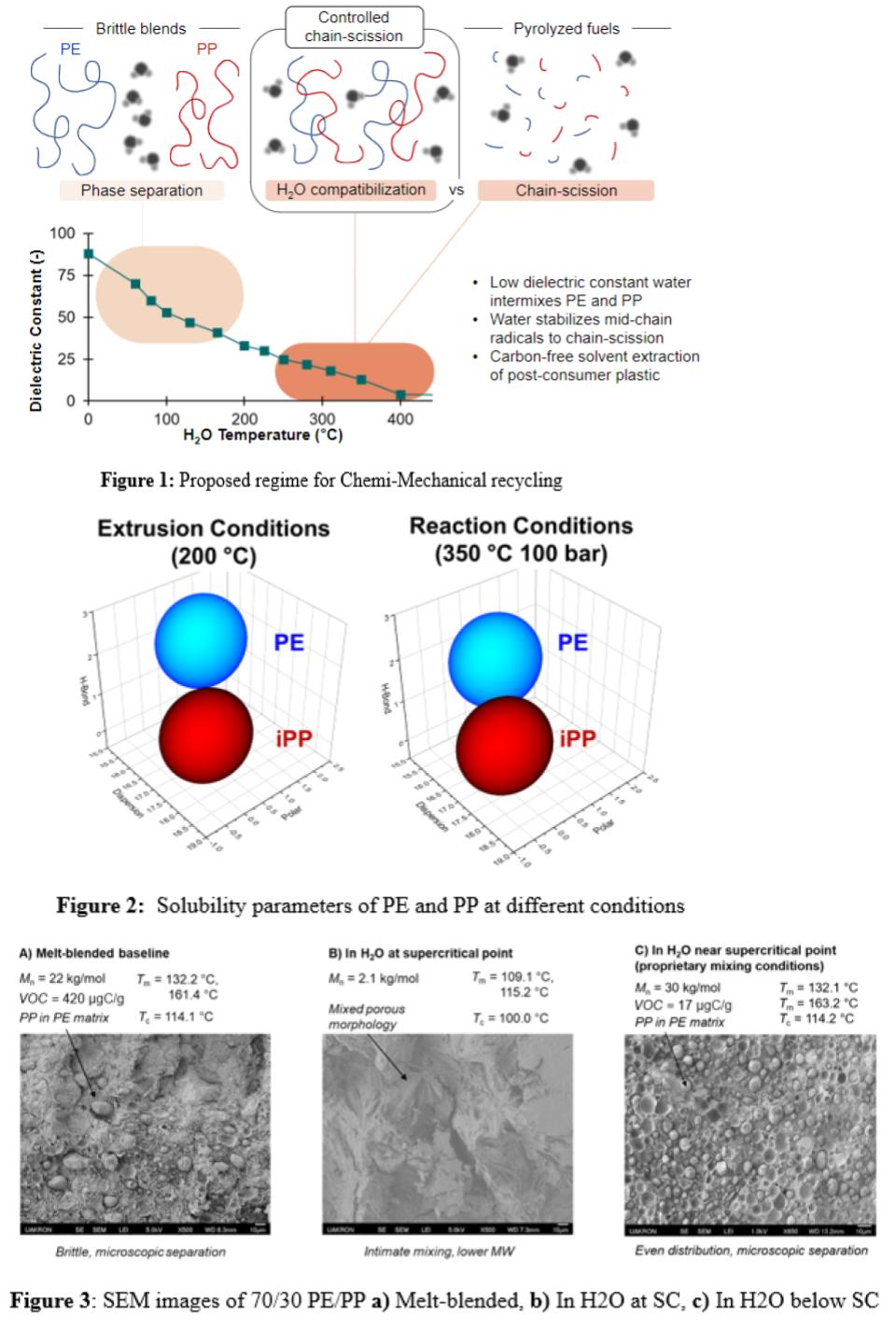

Plastic processing with affordable, environmentally benign solvents can solve the problems associated with the use of toxic organic solvents. The most abundant and least toxic solvent of interest is water. Room temperature water is a non-solvent for nearly all engineering plastics, meaning that it is useless for polymer recycling. Mild heating to melt the polymers in the presence of liquid water will achieve poor mixing resulting in brittle blends (Figure 1a). As shown in Figure 1d, the properties and especially the dielectric constant of water change with increasing temperature and dramatically near its critical point, to the extent that hydrocarbons are miscible with near and supercritical water whereas salts become immiscible in it. Unfortunately, water near its critical point is regarded exclusively as a solvent for deconstruction, as a multitude of literature reports attest. Harnessing the potential solubility properties of water seems infeasible at first glance, as shown in Figure 1c.

A common thread in the literature on near and supercritical water processing of polymers is the use of harsh conditions – high reaction temperatures, long reaction times, presence of co-reactants especially oxidants, and the presence of catalysts all promote complete conversion of the plastic to small molecules. Interestingly, however, hydrocarbons such as long-chain alkanes are known to be stable in near-critical water on the order of minutes or hours with minimal degradation – provided the temperature is sufficiently mild and no co-reactants are present. Polymers are unlikely to dissolve fully in water at the conditions where alkane stability has been reported. Instead, we hypothesized operating at an intermediate temperature between those required for deconstruction and those at which no blending occurs. The proposed regime can be seen in Figure 1b; under these conditions, water expands the polymer melts, allowing them to mix with one another. Within these melt phases, thermal reactions produce free radicals that can recombine with one another to promote molecular-level polymer-polymer blending. The processes that are hypothesized to occur in Figure 1b can be termed “chemi-mechanical recycling” as the resulting product bridges the industrial gap between upgraded pyrolyzed fuels and underperforming mechanical recyclate.

Two of the most commonly produced plastics, polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP), account for over half of all plastics produced but have very low recycling rates. Despite similar monomers, these two polymers despite are immiscible and blending by traditional means the results in product that suffer from poor interfacial adhesion and phase separation. This can be visualized using Hansen solubility parameters (HSPs). As seen in Figure 2, at extrusion conditions there is still a relatively high energy distance between PE and PP. As the spheres do not overlap, this means the materials are not soluble with each other. However, at temperatures greater than what is achievable in extrusion, the spheres overlap indicating the materials become more soluble in each other with increasing temperature.

A series of polyethylene and polypropylene mixed streams was treated under chemi-mechanical recycling conditions and analyzed. Figure 3a is an SEM micrograph that shows the morphology of PE/PP that have been melt blended via twin screw micro compounding. The resulting product maintains a high molecular weight but suffers from interfacial adhesion failure and has a high retention of volatile organic compounds (VOC) indicating impurities and slight chain degradation. The sample in Figure 3b underwent the chemi-mechanical treatment at the supercritical point (SC) of water resulting in a low molecular weight, but intimately mixed, Fischer-Tropsch like wax product. In 3c, PE and PP underwent the chemi-mechanical recycling process at temperatures below the SC point of water. The resulting product has a uniform dispersion of PP droplets in the PE matrix and a high retention of molecular weight.

An area of ubiquitous importance in plastics recycling is the removal of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Many mechanically recycled plastics have a high number of VOCs which limits the applications of this recyclate. This trend can be seen in 3a, the mechanically recycled blend which has a high VOC concentration of 420 µgC/g. Comparing to the chemi-mechanical recycled sample, 3a has over a factor of 20 more VOCs in the product. This significant reduction in VOCs indicates that additives may be extracted into the water phase making this process suitable for purifying post-consumer waste.

In summary, treatment of a PP-PE mixture in water near its critical point produces an intimately mixed blend which retains a high molecular weight and its original melting characteristics. Temperature conditions can be tuned from a regime in which neither blending nor degradation occurs through a regime at which blending occurs with minimal degradation to a regime at which both blending and degradation occur. The results presented here establish a previously undiscovered regime that combines chemical and mechanical recycling as a new approach to transform mixed plastic waste streams into a purified and compatibilized product.