2022 Annual Meeting

(2cr) Synergizing Molecular Simulations and Machine Learning for Understanding Molecular Interactions.

Author

Despite their importance, our current understanding of IDPs (also referred to as the âdark proteomeâ) is still quite limited. The technology for targeting IDPs via rational drug design is still in its infancy. In contrast to globular proteins whose functions rely on folding into stable structures, IDPs are dynamically disordered. A complete understanding of how an IDP works requires the knowledge of its conformational ensemble. Experimental observables are averaged over many disordered states and thus only provide a partial view of the underlying ensemble. With the ability to provide atomic information of conformational dynamics, molecular simulations naturally complement experiments and are invaluable for studying IDPs. Currently, challenges persist in using molecular simulations for understanding IDPs at several scales. At the atomic scale, making accurate predictions of IDP binding is still out of reach for atomic molecular simulations. At the mesoscale, it is still a challenge to predict if an IDP promotes phase transitions. Even more difficult is to discern the IDP components are essential for phase transitions. Moreover, conventional structure-centric drug design methods are inadequate for targeting IDPs because of the dynamic nature of IDPs.

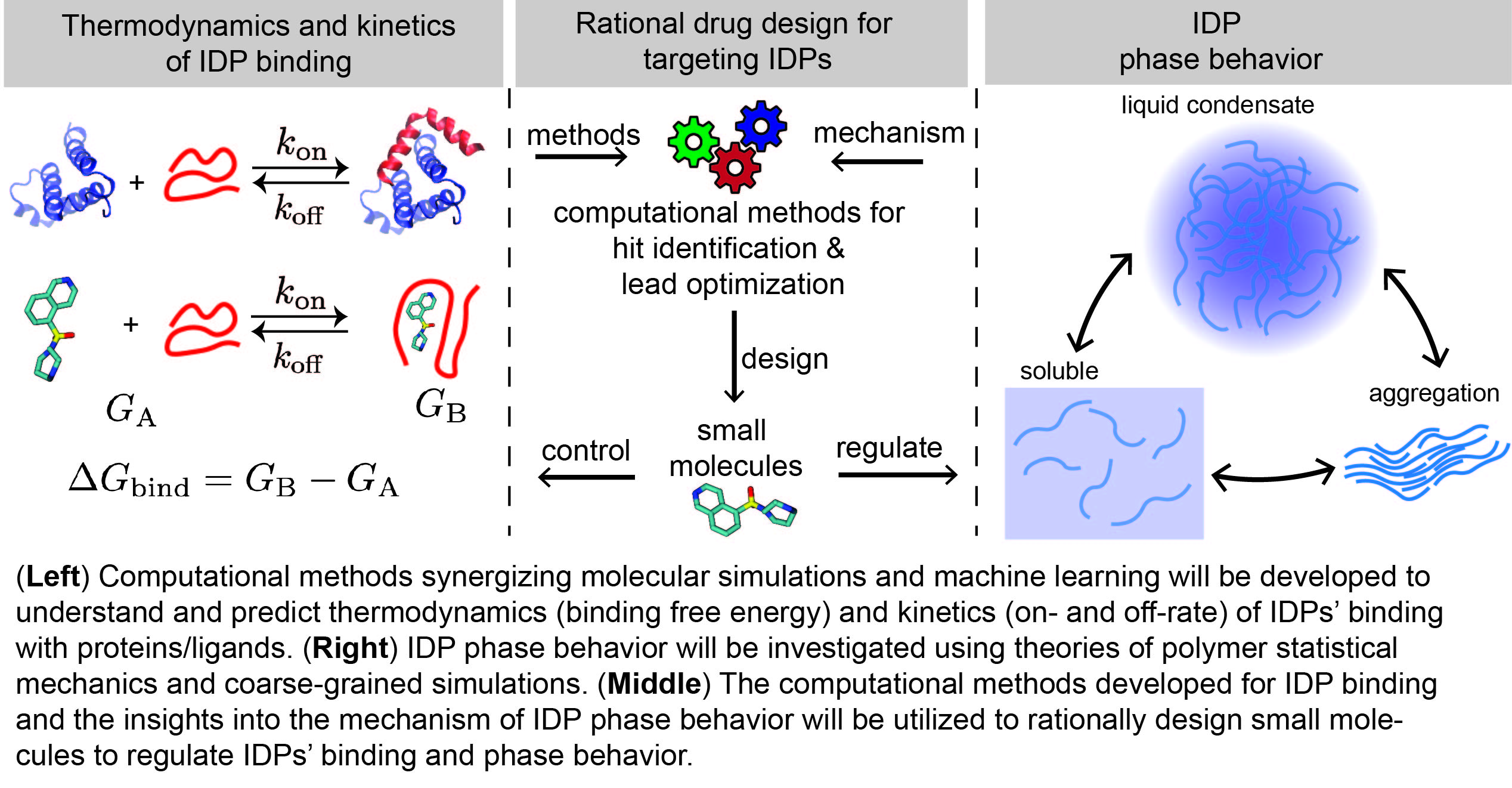

To overcome these challenges in understanding and targeting IDPs, I will develop novel computational models/methods by synergizing molecular simulations, statistical mechanics, and machine learning. The proposed research will enable accurate prediction of IDP binding and phase transitions and a deep understanding of diseases caused by IDP mutations. It will provide a basis for the rational design of small molecules that mediate IDPs for therapeutic purposes.

Understanding and predicting the binding of IDPs with proteins/ligands: IDPs regulate cellular signaling pathways by binding with nucleic acids and structured proteins. Compared to structured proteins, the binding of IDPs has more complex characteristics such as coupled folding and binding and binding with ligands via dynamic and transient interactions. The atomic mechanisms underlying these characteristics are not well understood.

To better understand IDPsâ binding with proteins and ligands, we need accurate and efficient methods to probe the thermodynamics and kinetics of IDP binding. Existing molecular simulation methods, developed for structured proteins, require a pre-defined collective variable describing the binding process. They have limited use in investigating the binding of IDPs because the collective variable governing IDP binding is not known and is most likely high dimensional. As a result, existing methods cannot efficiently and rigorously compute IDPsâ binding free energy. The problem is even more prominent in investigating IDP binding kinetics that also relies on collective variables. Methodological innovations are needed to overcome these limitations.

Studying IDP binding thermodynamics and kinetics requires modeling high-dimensional probability distributions, learning collective variables, and sampling free energy landscapes. Machine learning provides promising theories and algorithms for solving these problems but has not been fully explored. Specifically, both modeling high-dimensional probability distributions and learning collective variables are at the heart of unsupervised learning. Researchers in reinforcement learning have developed algorithms that balance exploration and exploitation for sampling an unknown landscape. Therefore, rigorously combining machine learning with molecule simulations presents an exciting opportunity to overcome the limitations and develop effective computational methods for studying IDP binding.

We developed DeepBAR for computing binding free energy by synergizing unsupervised deep learning and the free energy method BAR (Bennett Acceptance Ratio). DeepBAR is 50 times more efficient than current rigorous methods while maintaining the same accuracy. DeepBAR solves the longstanding problems of free energy methods at balancing accuracy and efficiency by eliminating the use of both collective variables and intermediate states. With further development, it will be very well suited for studying the thermodynamics of IDP binding. I will also use similar ideas to advance computational methods for studying the binding kinetics of IDPs. Understanding binding kinetics requires mapping and sampling of the entire binding landscape, which requires learning a low-dimensional representation of the landscape. Excellent choices for such tasks are latent state-space models, which have been successfully applied to images and languages but have not been explored for IDP binding. I will propose and implement new latent state-space models specifically designed for modeling IDP binding landscapes.

The proposed methodological developments will significantly enhance the capacity of molecular simulations for studying the binding mechanisms of IDPs with both proteins and ligands. They can not only help investigate the effects of various factors such as modifications and mutations on IDP binding but also shed new light on the design strategy of small ligands targeting IDPs.

Multiscale modeling of IDP phase behavior: Another characteristic of IDP binding is that IDPs transiently bind to multiple partners, which enables IDPs to play an essential role in promoting phase separation to form membrane-less organelles, also called biomolecular condensates. Recent studies suggest that, like organelles separated by membranes, biomolecular condensates created by liquid-liquid phase separation work as a general compartmentalization mechanism to organize cellular matters and reactions. Disorders in their formation and dissolution can lead to protein misfolding and aggregation, which are often the cause of aging-associated diseases. Deciphering the mechanism underlying these diseases requires understanding the physical nature of biomolecular condensates and how various factors, including pH, ion concentrations, and modifications or mutations on IDPs, affect their formation. Key challenges in studying biomolecular condensates include understanding how and why only some IDPs promote phase transitions, discerning essential components, and predicting the phase behavior of IDPs.

Although atomic molecular simulations such as those proposed above are useful in studying the detailed mechanism of IDP binding, they cannot reach the spatial-temporal scale of phase separation to address the questions mentioned above in understanding biomolecular condensates. As shown in previous studies, maintaining a fully atomic representation might not be necessary, or even desirable, to connect simulations with experimental observables, providing important interactions for IDP phase separation are accurately modeled in a simplified representation. Coarse-grained (CG) models, as one type of simplified representation, have been essential for simulating processes that are not accessible for atomic simulations. To study biomolecular condensates using a CG model, the CG model must accurately capture the interactions among condensate components, including nucleic acids, structured proteins, and IDPs. More importantly, to make accurate predictions on the effects of various perturbations, the CG model has to be transferable to different biomolecular condensates under multiple conditions. However, existing CG models for modeling biomolecular condensates have limited transferability. To systematically study the phase behavior of IDPs using simulations, I propose to develop a transferable CG model of biomolecules that would enable accurate quantitative predictions on biomolecular condensates.

Two sources of information can be used to construct a transferable CG model: atomic force fields and experimental data. Atomic biomolecular force fields have been built with decades of research efforts and tested to have good transferability. Simulations using atomic force fields can provide initial reference conformation ensembles as the objective for CG models1 to reproduce. Experimental data can be used to fine-tune learned CG models to correct errors that might exist in atomic force fields. To maximize its transferability, the CG model has to be simultaneously parameterized on as many biomolecular systems as possible using both sources of information. Existing computational methods for learning CG models often require iterative optimization and are not scalable to many nucleic acids and proteins.

We proposed a new scalable method for learning transferable CG models by combining noise contrastive learning with the maximum entropy principle. The proposed method has the following advantages. (i) Using noise contrastive learning, it can learn many-body potentials that might be required in CG models. (ii) It only requires one round of optimization instead of iterated optimization, making it applicable to learning transferable CG models based on many biomolecules. Our preliminary results have confirmed these advantages. Moving forward, I will identify many biomolecule systems for which experimental data exist and long-timescale atomic simulations are feasible using GPUs. Based on these systems, I will use the proposed method to build a transferable CG model for biomolecules including nucleic acids, structured proteins, and IDPs for studying biomolecular condensates and how various factors affect their formation. These studies will help us understand the mechanism of abnormal protein phase behaviors associated with neurodegenerative diseases and identify IDP targets for drug design.